Market Economics

Australian residential construction is in decline | by Flavia Santia

Australia is a country with a solid and dynamic economy that has maintained steady GDP growth over the last thirty years, making it necessary to modernise the country’s infrastructures and territories in step with the continuous growth in population and expansion of commercial activities.

These factors have been accompanied by a process of global economic and commercial integration, resulting in the creation and implementation of long-term plans which in turn open up major trade and investment opportunities for Italian companies.

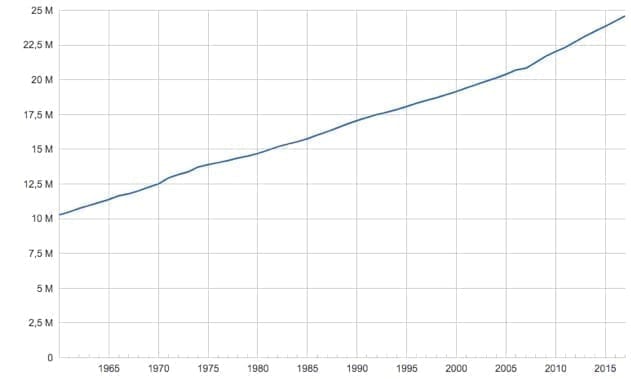

One of the biggest contributions to the economic boom has come from the unprecedented population growth (Fig.1) (around 200,000 more people each year) and the concentration of citizens in the major cities (Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth). Investments in infrastructure, transport and housing have rapidly become the top priority. The most popular destinations are not limited to the area around Sydney, which nonetheless remains at the top of the list of destinations for both travellers and workers, but includes the whole of Australia. This trend is fuelling a significant increase in the demand for housing and services throughout the entire country and consequently creating new opportunities for people working in these sectors.

Fig.1: World Bank

In contrast with the growth in non-residential construction, residential housing has suffered a slow but steady decline over the last year and a half due to excess supply with respect to demand. Nonetheless, the projections see the sector returning to growth in the next few years on the back of rising demand, income growth and a greater need for renovations. (In particular, from 2016 onwards it has been estimated that between 500,000 and 700,000 homes are needed in each of the major Australian cities.)

However, the real issue facing the housing sector is the risk of it failing to achieve the transition to sustainability.

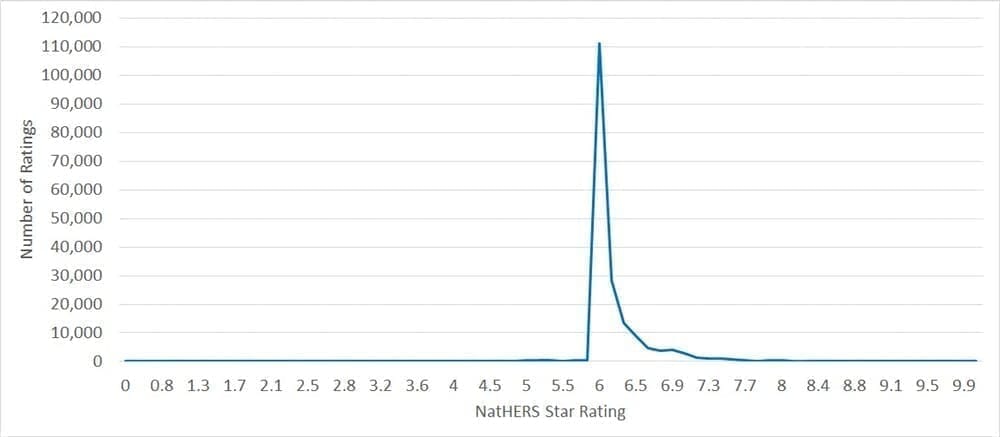

Contrary to expectations, in Australia the transition is taking place very slowly and the results are far from optimal, although so-called green houses may represent new sources of investment, opportunities and growth. To determine the sustainability of a home, it is necessary to consider its energy performance in terms of carbon emissions, which must always be greater than or equal to the minimum value permitted by the country’s policies. In Australia the standard is set by the Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHers), a system that rates the energy efficient of a home on a scale from 1 to 10. The minimum level for Australia is 6, lower than the value set by many other countries. This means that the number of highly energy inefficient homes has multiplied in parallel with the building boom. A study carried out by the Journal of Cleaner Production, “Barriers inhibiting the transition to sustainability within the Australian construction industry: An investigation of technical and social interactions”[1] demonstrates the existence of certain practical difficulties that partly hinder the transition. However, it also shows that the biggest responsibility lies with the behavior of various stakeholders and interest groups involved in the process, who profit from delaying the transition rather than implementing actions towards sustainability.

Further research by Trivess Moore, (RMIT University), Michael Ambrose (CSIRO) and Stephen Berry (University of South Australia)[2] has found that only 4 out of 5 homes exceed the minimum standard set by NatHERS. Despite actions aimed at raising the minimum level, it appears that the stakeholders have been reluctant to do so, confident that market forces would fuel demand for green solutions. The standard was set at 6 almost eight years ago but the push from the market has never occurred, as a result of which only 1.5% of the homes taken into consideration exceed the minimum level. Consultation of NatHERS data for homes built in Australia between May 2016 and December 2018 has shown that out of the 187,320 homes considered, more than three-quarters of them gravitate around the minimum standard. (Fig.2)

Fig. 2: NatHERS star ratings across total data set for new housing approvals, May 2016–December 2018.

Source: Research by Trivess Moore (Lecturer, RMIT University), Michael Ambrose (Research Team Leader, CSIRO), Stephen Berry (Research fellow, University of South Australia)

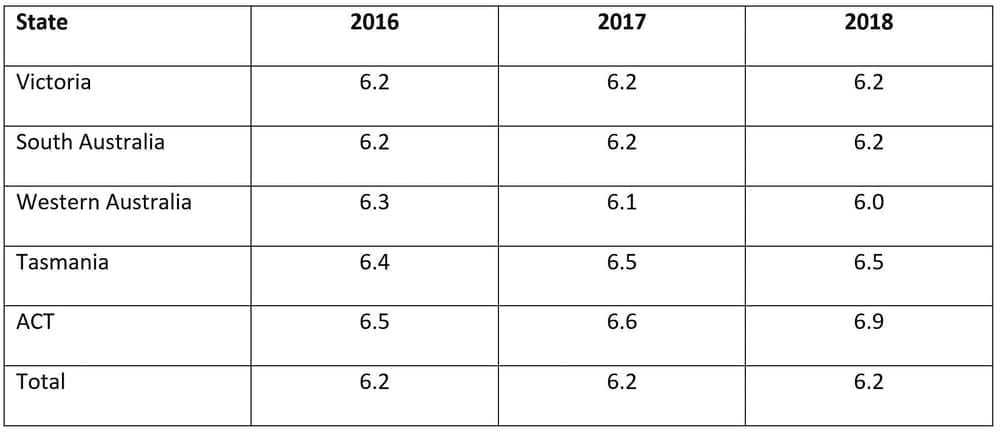

As the data show (Fig.3), the same conclusion is reached when considering a nationwide average.

Fig. 3: Average NatHERS star rating for each state, 2016-18

Source: Research by Trivess Moore (Lecturer, RMIT University), Michael Ambrose (Research Team Leader, CSIRO), Stephen Berry (Research fellow, University of South Australia)

What the research really shows is that sustainable housing construction conditions could be improved simply by raising the minimum standard of efficiency. It follows that the outcome of the transition is determined not by consumer behavior or an awareness of the optimal energy level but by the regulatory level. Consumers accept what is available on the market and passively accept the minimum standard.

In the long run, this mechanism will only increase costs as it is not just homeowners who benefit from an energy-efficient system but society as a whole. The reason why citizens are not made aware of the positive aspects of energy efficiency is that the process is obstructed by stakeholders, despite the fact that the environmental and economic harm caused by energy waste is increasingly clear to the public. This being the case, increasing the minimum standard would appear to be the only solution.

The causes of this difficult transition also lie on the demand side. According to an in-depth analysis entitled “End-user engagement: The missing link of sustainability transition for Australian residential buildings”[3], commercial building owners are the only ones who are really interested in green buildings and are convinced about their benefits and economic returns. Owners and potential buyers of housing have received no encouragement at all to contribute to the transition to sustainability. This means that improving construction techniques or tools for assessing sustainability will be of little use if the other side of the market is not convinced of the advantages.

The proposed solution is to support and implement demand from end users in order to stimulate the supply side and encourage government action, which could be achieved by providing incentives for sustainable home purchases. This solution would meet the interests of several actors: buyers would be encouraged to choose green solutions; the government would get closer to achieving its sustainability goals; future generations would not be affected by the economic damage of our carbon emissions.

The Australian residential market has so far been neglected in the study of the construction industry, but certainly deserves more attention as it represents a fundamental part of the overall picture and is also a source of endless opportunities and investments for local and foreign companies.

January 2020

[1] (Marteka, Hosseini, Shrestha, Edwards, & Durdyev, 2019)

[2] (Trivess Moore, 2019)

[3] (Marteka, Hosseini, Shrestha, Edwards, Seaton & Costin, 2019)