Interviews

Designing the invisible | by Alessandra Coppa

In marked contrast to the extravagant global style architecture that dominates Milan’s constantly-evolving skyline, the more measured interventions carried out by Asti Architetti integrate with the urban fabric like homeopathic remedies.

The residential conversion of a number of historic buildings in Milan’s city centre previously used as offices provides an opportunity to reflect on the work of architects and the contribution of Italian professionals in the age of globalisation.

The rules of good building practice, together with a keen awareness of the sense of “urban decorum” in the tradition of the masters of Milanese Modernism, underpin the design approach followed by Paolo Asti, who has carried out numerous projects in the centre of Milan.

Paolo Asti’s work focuses mainly on remodelling the existing building stock and adapting old buildings to meet the needs of contemporary living and the demands of the market. His is a non-gestural form of architecture that identifies a new “normality”. We met him in his Milanese studio in Via Sant’Orsola.

I read that your design philosophy focuses on the “organicity of a building with a view to building renovation”. What do you mean by this?

Throughout my professional life, I have almost always worked on the existing fabric, in a highly stratified context in which I can operate freely. My work starts out from an existing building, which will perhaps be demolished and then rebuilt from scratch but which is nonetheless part of the existing fabric.

I use the word “organicity” to refer to the process of adding value to a work of architecture in all its complexity and over its entire “life cycle”. This means not just technical performance and compliance with regulations, which have evolved or changed over time, but also aesthetic impact.

As I work on building renovation projects in the real estate market, all my buildings are intended to be sold or let. Because they must appeal to a prospective customer, it is vital to keep down costs not only during construction but for the entire lifetime of the building. I would say this has become the overriding consideration in the design phase.

The idea of “giving new life” to a building is a very interesting one, especially in Italy and in Milan where most of your projects are carried out…

In my opinion, the new frontier in the Italian real-estate business is not constructing new buildings but giving fresh life to the existing building stock.

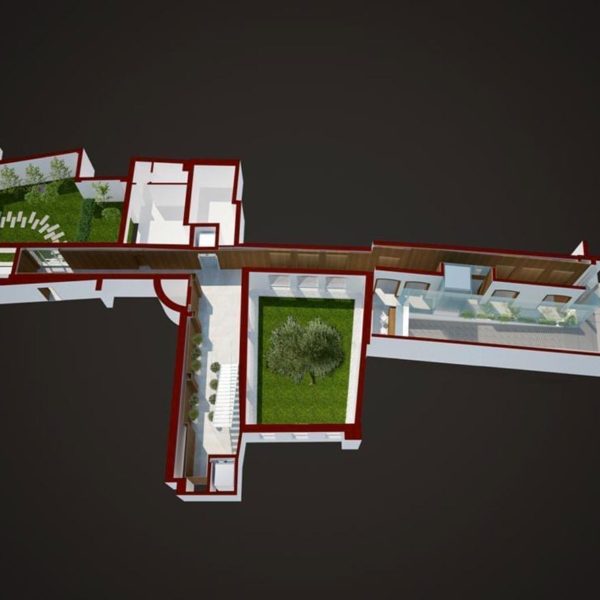

Based on this premise, most of my practice’s work is in the historic centre of Milan. In particular we concentrate on renovating and re-functionalising historic buildings that date back to periods when criteria and regulations were very different, and attempt to comply with today’s building regulations and living requirements as closely as possible.

Many of Milan’s buildings are obsolete, not just in terms of their external morphology but above all with regard to their intended use.

Milan was one of the first Italian cities to attempt to combine compatible intended uses, a major achievement dictated by market forces which has influenced the rest of the country.

It seems to me that the works of Asti Architetti serve as “homeopathic” remedies for the urban fabric, high-precision interventions without any kind of “gestural” intention.

Most of my practice’s projects are located in the centre of Milan. Typically they consist of inhabited properties where an investor has decided to carry out a renovation project aimed at increasing the value of the building.

This market trend began in about 2000 and coincided with the opening of my practice.

The real-estate sector has seen a significant change in mentality because people have come to realise that renovating a property can increase its value enormously in market terms.

But to do this it was necessary to choose the right intended use.

Real estate trends follow precise socioeconomic cycles. For example, between 2000 and 2010 I completed numerous projects that involved converting high-quality city centre office buildings to residential use. This coincided with the trend of moving offices to dedicated islands outside the city centre as part of the focus on business centres that is now in vogue in Italy.

This trend in the 2000s to restore the residential function of the city centre received further impetus when historic buildings owned by banks were freed up and subsequently converted to residential use. The real estate market underwent enormous growth in Milan between 2008 and 2010.

In Milan you have renovated buildings in Via Cusani, Via dell’Orso, in Foro Bonaparte, in Largo Cairoli, in Via Borgonuovo and in Via Moscova… Could you tell us about a project you consider to be particularly significant?

It’s really hard for me to choose one in particular. A project which I found really interesting – not in terms of the success or otherwise of the architecture itself but from the point of view of the approach I was talking about earlier – was the one carried out for Banca Generali in Via Moscova 58.

Our aim was to make the building look new even though it was built 50 years ago and to treat the façade in such a way that it could be reintegrated into the city centre. The project had to be inexpensive, and we had to make best use of the building regulations so as to increase the volume. Moreover, it had to be possible for at least 50 percent of the tenants to continue to live there while the work was being carried out.

Ceramic tiles are particular useful for this kind of project because the tile industry has succeeded more than any other sector in catering for the kind of situation imposed by the market, in other words the need to work on existing, inhabited properties with limited budgets.

What contribution can ceramic tiles make to this kind of project?

There are products that have been specially developed in order to maintain the existing structures and surfaces without the need for radical technical changes. Ceramic tiles are ideal in this respect, especially given their dimensional flexibility and very large sizes and their unique combination of aesthetic quality and ease of installation. I often specify large-format ceramic tiles when embarking on a project and keep this finish in mind right from the start of the design process and throughout all subsequent steps. Professionals like us working in the field of real estate design need to adopt this kind of approach.

Do you think the ceramic industry offers versatile products for architectural design?

Ceramic tiles now come in an enormous variety of shapes and sizes. It’s an exemplary industry that has reinvented itself very effectively after reaching a bit of a dead-end. Historically, ceramic tiles had always been considered an extremely hard-wearing and easy-to-clean product suitable mainly for use in kitchens and bathrooms. Now, however, they have opened up new fields of application thanks to their improved technical characteristics and the development of new surfaces such as imitation stone and marble that are genuinely capable of increasing the prestige of spaces. Although these imitation materials have often been seen in a negative light and not really accepted by architects, I can assure you that people think differently when they have to sell a building taking account of durability, cost and aesthetic quality.

In fact there has been much talk of the relationship between natural and artificial and the “new artificial” proposed by ceramics.

Some people are against using a material that imitates another, but we should always remember that the use of stone or marble depletes the natural environment. Avoiding excessive use of these materials not only helps the environment but is also common sense.

The use of ceramic tiles that imitate wood or stone brings high-quality results.

Work will soon begin on the renovation project for The Big Hotel for Unipol in Milan Porta Nuova, for which we have proposed the use of ceramic tile as the finishing material throughout.

Does this rule of maintaining a kind of normality and avoiding architectural gestures at all costs also apply when designing a façade?

I am always very respectful when choosing a façade and take into account the fabric of the city that has been built up over the years. Façade cladding operations are mainly cosmetic and are aimed at improving the city and promoting urban decorum. We architects must reclaim an urban language that takes account of the basic principles of our profession.

So paradoxically your identity, your stylistic hallmark is the lack of visibility of your projects within the urban fabric?

Yes, that’s true, although I must say that the buildings that people talk about and which remain impressed in people’s minds are those that are very iconic, that are designed to be spectacular right from the outset. However, this kind of architecture is the result of globalisation and can become a kind of affectation. I think there’s something fundamentally wrong if a project carried out in New York also works fine in Dubai. This “global style” trend that is currently in vogue in Italy is destructive. We have such a strong architectural tradition that we are adapting to other styles and not the other way round. Instead, we must remain faithful to the building design methods that have become established over the years.

Biography

Asti Architetti, now located in Via Sant’Orsola 8, works on both residential and commercial projects and specialises in architectural design, focusing in particular on the organic nature of buildings and renovation projects.