Interviews

Learning from the masters | by Alessandra Coppa

“I created a number of items for companies that had collaborated with masters of design, such as Montina, Fontana Arte, Poltronova and Oluce… I chose to proceed respectfully, almost on tiptoe, but without being afraid to do something new.”

Architect and designer Timothy Power arrived in Italy in 1990 after receiving an invitation from Ettore Sottsass to work in his studio in Milan. Born in Santa Barbara and raised between Northern and Southern California and Hawaii, Tim was at that time working on a project for the Tech Museum of Innovation in Silicon Valley for the San Francisco-based studio A+O. At Sottsass Associati he became part of an experimental international team and worked on a range of design and urban-scale projects, exploiting his two years of experience in the radical architecture movement at Superstudio in Florence.

Could you tell us something about your rather unusual background, from studying at American universities to the Milan Polytechnic and then your experience with Ettore Sottsass?

Before starting up my practice I was involved with the Superstudio multidisciplinary group in Florence during the post-radical period, after which I also collaborated with Gianni Pettena and Sottsass in their heyday. I began my education at a highly technical institution, the California Polytechnic State University, then in Italy I came into contact with a world that touched on art and society, land art and body art. In the late eighties and early nineties, Milan was a major centre for this fusion of the arts. Gregotti’s rigorous school of thought coexisted with the more transgressive approach taken by Sottsass, and at the same time Citterio and Lissoni were also setting up their practices. It was a small, closely-knit world where architects all knew each other and there was plenty of work. Perhaps it is only now that Milan is returning to that kind of vitality after a number of difficult years.

What do you remember from the years spent working at Sottsass’s studio?

I arrived in Milan in 1990 and worked with Sottsass in his studio in Via Borgonuovo. One of the most important things I learned from Ettore and from that experience was without doubt his transversal approach combining architecture with the art world – not just in terms of visual art but also aesthetics. Despite the fact that I ended up changing direction when I started up my own practice, the years spent with Sottsass were very formative.

In what way?

I didn’t assimilate his style, only the conceptual values that are expressed in his works, and this complemented my technical training. Sottsass valued the ingenuity and energy of young people, their desire to change the world. His confidence in the younger generations and his preference for jobs that were not technically complex was something I very much appreciated. Then in 1996 I opened my own studio without having a single client. I don’t know if it was through courage or recklessness! And although I had been involved in architecture projects at Sottsass’s practice, I began working in the design sector for several small Italian, Scandinavian and Japanese furniture companies, simply because the field of design was much more open to foreigners.

What was your first project?

My first project was Chip Chair for the company Zeritalia. It took me four hours of frenetic work to create something that was the precise opposite of Ettore’s way of thinking… and then it was suddenly published everywhere! I then worked with my close friend James Irvine on the design of a Mercedes Benz bus, a wonderful job for the city of Hanover. Then Sottsass – who was very generous even with former co-workers – passed me an assignment for WMF, a German company that produces cutlery and saucepans, and put me in touch with a ceramic company called Cedit, which wanted to produce a line for the Asian market. These projects enabled me to survive at the beginning of my career.

Besides Sottsass, you have often been involved in projects that touch on the work of other great Italian architects, such as the restyling of Franco Albini’s Rinascente building in Rome and Achille Castiglioni’s Palazzo della Permanente in Milan.

For the renovation of Albini’s Rinascente building in Rome, we were asked to carry out a fairly radical intervention that involved altering the circulation flows. This was very difficult because our normal approach in the case of iconic works of architecture like this is to avoid excessively altering the original aesthetic appearance. However, Albini simply didn’t have the technologies that are available today so to bring the building up to the necessary functional standards we had to renovate it. We didn’t want to touch the stairs designed by Albini but we did upgrade the technology and tried to “reknit” the façade and other elements of the building as respectfully as possible. I renovated several floors while attempting to keep my intervention to a minimum so as to preserve the original spirit of the building. We followed the same approach for the Museo della Permanente in Milan, where we created numerous spaces for temporary exhibitions. In one of these interventions we uncovered traces of the original work done by Castiglioni. After the exhibition, the Museo della Permanente asked us to leave these traces exposed, which we did.

Which are your most significant projects?

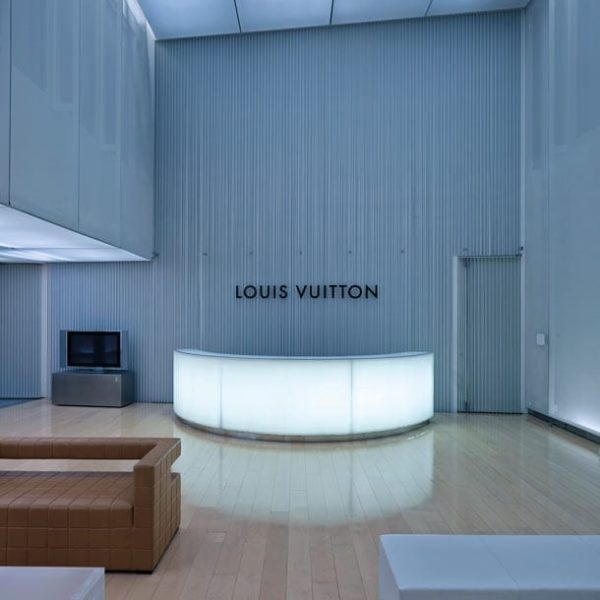

My career has proceeded in a number of major steps. In the early years it was far from easy for a foreigner to enter the world of architecture. In Milan there were only a few firms that worked on large-scale projects. So I started out by focusing on the world of design, particularly furniture, but at a certain point I had to make a choice. At that time, but already from the 1950s onwards, Italian architects tended to work on all scales “from the spoon to the city”, and the reason I had come to Italy in the first place was to be able to do a bit of everything. After starting out with furniture as my main line of work, I subsequently turned to the world of interior design. I worked for the Louis Vuitton group, mainly in Asia, restyling their standard furniture and interiors while at the same time continuing to work in the field of design. For example we created contract furnishings for Cassina and B&B.

In 2005 you designed a very beautiful chair for Montina…

The chair is called T1 and the company Montina, founded by the Montina family with Gio Ponti as art director, was a very important company. I also created a number of items for other companies that had collaborated with masters of design, such as Fontana Arte, Poltronova and Oluce. Here too, I proceeded respectfully, almost on tiptoe, but without being afraid to do something new.

Have your ever worked on architectural design since your experience with Sottsass?

After collaborating with Vuitton, we did a lot of work in the world of retail and interiors in Japan. Following this experience I wanted to return to architecture, to creating buildings. However, in Italy I have only done small jobs. We’re also taking part in competitions, such as the one for the Porta Nuova area in Milan in collaboration with the Dutch firm West 8, where we focus on the idea of water and the Navigli canals. We often collaborate with firms that are more structured than ours so as to be able to take a “directorial” approach with large-scale strategies.

Regarding your work with ceramics, earlier on you mentioned your collaboration with Cedit.

We designed a collection that would be produced in Italy for the Asian market with the idea of selling it through major retail outlets in China. In the late 1990s, the Chinese wanted to buy Sottsass’s collection at much lower prices, but that was simply not possible. For Cedit we designed a floral collection with geometric and abstract lines, softer than those proposed by Sottsass.

Did that work continue?

About ten years ago I collaborated with Provenza Ceramiche alongside other designer friends such as Konstantin Grcic and Fabio Bortolani. The company was starting up production of 3 by 1 metre porcelain panels and asked us to experiment with different ways of using their products. This highly abstract, clean line was called Landscape. Now there’s this idea of reproducing natural textures, stone and marble …

What do you think of this trend of ceramic imitating other materials?

I think it’s very interesting. Although real marble and wood are exceptional materials that gain in beauty over the years, there are simply not enough natural products available for use in projects. In the field of ceramics I particularly love stoneware, it’s a material that ages very well.

BIOGRAPHY

In 1996 Tim Power founded Tim Power Architects and carried out architectural and design projects in the USA, Europe and Asia.

He has worked on shops, offices and workspaces for clients including Louis Vuitton, Motorola, Texas Instruments, Muji, J Walter Thompson and UCI (Paramount Pictures), designing and building the interior architecture of complete buildings.

In the field of design he has created industrial products, furniture and objects for FontanaArte, Oluce, Poltronova, Rosenthal, Mitsubishi, Cassina/Interdecor, WMF, Montina, David Design, BRF and Alfi.

His work in the field of culture includes exhibitions and installations for the Venice Biennale, the 1999 St. Etienne Biennale of Design, and the Triennale in Milan, where in 2016 he curated the section devoted to design from Asia at the 21st Triennale International Exhibition.

He has collaborated with international practices such as West 8, Akihiro Hirata, Sou Fujimoto Architects, 8 Inc., nendo, Jun Aoki & Associates, Rosemarie Trockel, SWA Group, Foreign Office Architects, James Corner Field Operations, Junya Ishigami, Toyo Ito, Sam Hecht and Morphosis Architects on projects, proposals and architecture competitions.

May 2018